‘No-Fault’ Divorce Bill: Head of Family law Jane McDonagh writes thought leadership piece for FT Adviser

Last week, the Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Bill passed through its first Commons debate with 231 votes to 16 against. Partner Jane McDonagh, Head of SMB’s Family Law team, writes for FT Adviser:

“Without question, the planned change to no-fault divorce will reduce the emotional cost of separation and brings the law into line with modern life.

But it will not a be a silver bullet, and there is still much work to be done to eliminate more of the unnecessary havoc caused by divorce.

No-fault is a great start, but we need also to look at the broader questions of how to deal most equitably with financial disputes (and in particular to consider the role of pre-nuptial agreements in our jurisdiction).

It is being heralded as the biggest shake up in divorce law for over 50 years

The Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Bill (commonly referred as the no-fault divorce bill) has passed its third reading in the House of Commons and will next be considered by the House of Lords.

It is estimated to become law by Autumn 2021. It is being heralded as the biggest shake up in divorce law for over 50 years.

It is widely believed that the catalyst for the new law was the case of Owens vs. Owens in July 2018, in which the Supreme Court reluctantly ruled against a petition by the 68-year-old Tini Owens to be allowed to divorce her husband.

The unhappy Mrs Owens was told that she was to remain married to man she no longer loved until they had lived separately for five years in 2020. At which point she was free to move on with her emotional and financial life.

Since 1969, married couples have only been allowed to divorce for one reason – that the marriage has irretrievably broken down.

The new Divorce Bill does not seek to change this fundamental principle, but it will change what qualifies as irretrievable breakdown.

As the law stands

As the law currently stands, a person seeking to divorce has to wait for two years if their spouse consents to the divorce or five years if their spouse does not consent.

If you do not wish to wait this long, the only way to divorce is to establish that your spouse is guilty of either adultery; unreasonable behaviour or (rarely these days) desertion.

This has to be done right at the outset of the process and crucially often sets a negative emotional tone for the subsequent financial negotiations and discussions regarding childcare.

This does both the family concerned and society as a whole a serious disservice, and although the planned changes are not a silver bullet, they should help reduce the harm that divorce can do.

Historical divorce

Society has changed significantly since the current divorce regime was created.

Today families come in many forms. Many couples cohabit rather than get married, children born out of wedlock are commonplace, couples can opt to enter a civil partnership as an alternative to marriage and marriage is now open to all couples regardless of their sexual orientation.

Importantly, there is also less stigma associated with divorce today since it affects nearly 50 per cent of all marriages.

Historically, however, a divorce was considered a rare and scandalous occurrence.

Before the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act, divorce was generally only available to men and granted by an Act of Parliament (which as you might imagine was extremely costly to obtain, and so only accessible to those of significant means).

The 1857 Act introduced statutory divorce which was open to both men and women (although for women to divorce they had to not only prove their husband’s adultery, but also couple this with other faults such as rape or incest). In the early 20th century, around 0.2 per cent of marriages ended in divorce.

After WW1, further reforms were introduced via the Matrimonial Causes Act 1923 which sought to make it easier for women to ask for a divorce even if they still had to prove adultery. Then in 1937, three additional grounds were recognised: desertion for two years or more, cruelty or incurable insanity.

The Divorce Reform Act 1969 was the last significant shift in divorce law and is the basis of the current legislation.

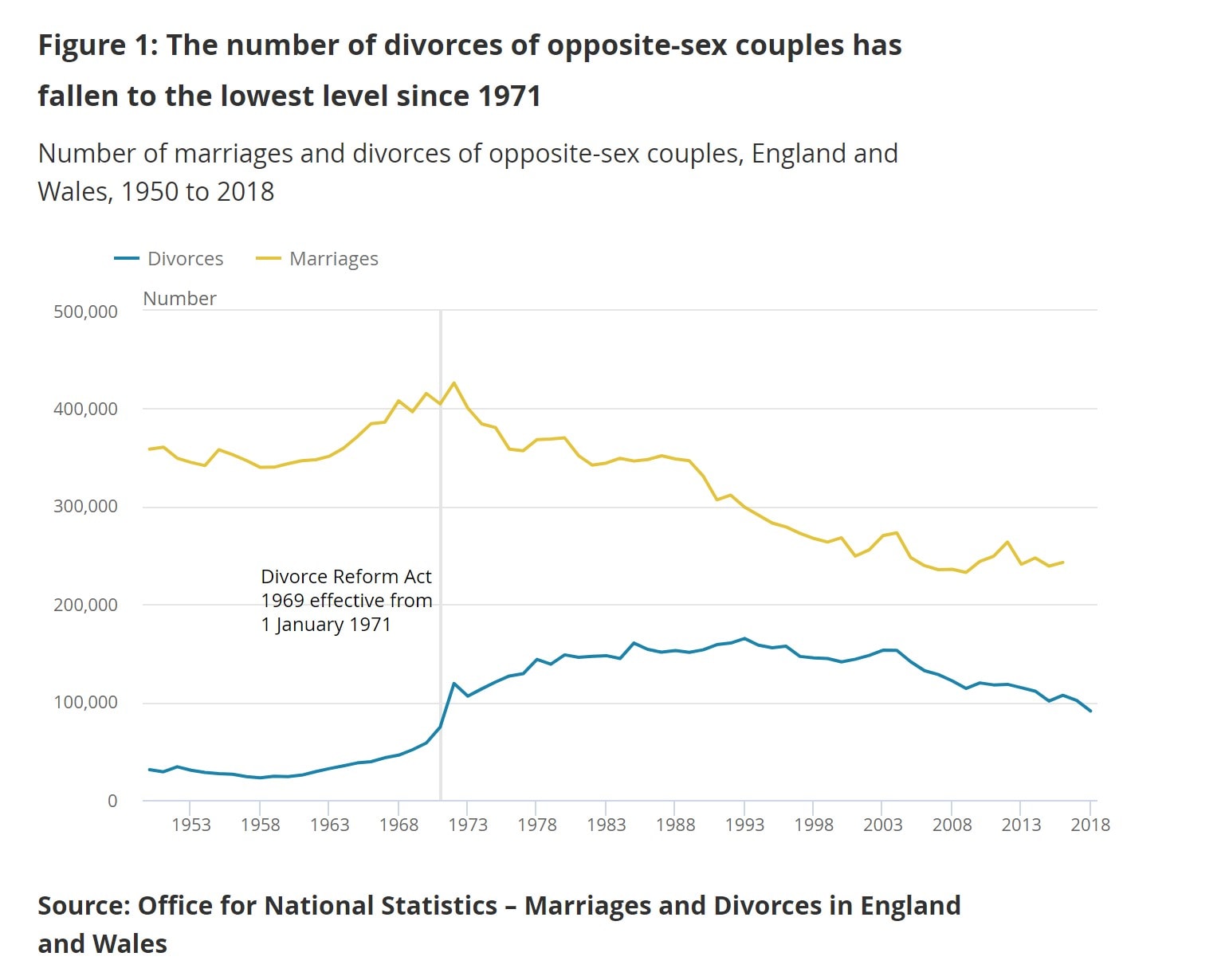

Inevitably, broadening the grounds for divorce alongside changing attitudes saw divorce rates double in a few years in England and Wales from 51,310 in 1969 to 106,003 in 1973. Two decades later divorce rates had increased to 165,018.

The latest data on divorce from 2017 actually shows a steady decline in the number of divorces – although this is at least partly because the rate of marriage has fallen by over 30 per cent over the last 40 years.

There was an attempt to introduce no-fault divorce in The Family Law Act 1996, but pilot schemes failed and the relevant sections of the law were repealed.

So, it was not until 2016, when the need for reform of the law was brought into sharp focus by the case of Owens v Owens. Mrs Owens petitioned for divorce on the basis of her husband’s unreasonable behaviour.

The husband contested the divorce and denied her (actually quite anodyne) allegations. Mrs Owens was therefore allowed to amend the petition to expand on the examples of her husband’s behaviour. This she did, listing 27 examples including that he disparaged her in front of others.

Despite the judge at the first hearing finding that the marriage had irretrievably broken down, it was held that Mrs Owens had not proven the fact of the husband’s unreasonable behaviour and therefore she could not proceed with the divorce. The Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court upheld this decision.

As a result, the unfortunate Mrs Owen had to remain married until 2020 to a man with whom she had no intention of reconciling (at which point they would have lived separately for a continuous five-year period).

The Lord Justices, led by Justice Lady Hale, called on parliament to consider whether the law governing the entitlement to divorce was satisfactory.

The Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Bill 2019-2021 is the result and the new law will allow for a couple to apply jointly for a divorce, or where the couple can not agree, allow one party can apply on their own.

The applicant simply has to provide a sworn statement confirming that the marriage has broken down irretrievably, and it cannot generally be challenged.

In a praiseworthy move, the language used by the Bill also aims to increase accessibility by using words such as a divorce application and order rather than the current petition and decrees.

Cooling off periods

However, there is a sting in the tail. The current wording of the Bill proposes cooling off periods at intervals – so that all in all there is a mandatory six months from beginning to end.

There is even a suggestion – though not confirmed – that the cooling off period will be extended to one year and it will be impossible in some cases to make applications concerning financial issues until after the cooling off period has ended.

If this comes about then it will in some circumstances significantly extend the time it takes to get a divorce and increase the cost. It would appear that these delays have been deliberately included not least to prevent an unseemly rush to post-lockdown divorce.

It is true, of course, that Covid and the extended confinement has tested, even if only momentarily, all but the strongest marriages.

In China, the authorities have felt it wise to impose a cooling off period of 30 days for their own couples currently keen to spend any second surge of the virus in different company. Even though Chinese citizens are well used to an interventionist government this has proved a very unpopular move.

It is also true to say that in the vast majority of cases, people go through a great deal of thinking before they reach the point of petitioning for a divorce, and at that point they are pretty resolute in their decision.

Of course, the decision is complicated and the implications will reverberate for some time, often through several generations. However, by the time our clients speak to us they have usually been through a lot of soul searching.

They are understandably keen to proceed and to conclude the divorce so that they can move on with their lives.

If there is a modicum of doubt as to whether they are certain about their decision, couples counselling is available and certainly will be encouraged.

For those couples that there is hope of a reconciliation, this is often achieved in counselling, and almost always prior to issuing court proceedings.

After the application is issued however, the law should allow couples to move forward at their own pace towards their chosen outcome

So the new law is a big step forward in acknowledging the fact that people grow apart, find different needs as they get older or for a whole bucket load of reasons find their plans have changed.

That is just human nature. Most of us see significant changes in every other aspect of our lives over time – friendships, careers, interests, family. And the new law reflects this is often the reality in marriage as well.

That said, divorce and separation is rarely going to be easy, nor given the often-serious consequences, should it be. We need to look at some of the other unhelpful and often hurtful challenges that remain, notably arrangements for children and division of money.

Certainly, the next area ripe for reform is the division of money and assets.

The courts have a significant level of discretion when deciding who gets what on divorce to reflect the complexity and diversity of human existence and provide the necessary flexibility to bend to the facts of each case.

It is difficult to say how fair a system can be if, as is the case, the results are so difficult to predict

For the many individuals who choose this jurisdiction for a divorce, this flexibility to take circumstances into account is seen as the quality of British fair-play.

In other countries, courts are restricted by inflexible rules as to division of assets and ongoing maintenance which undoubtedly sometimes lead to arbitrary and unfair results.

However, it is difficult to say how fair a system can be if, as is the case the results are so difficult to predict. The court process will always involve uncertainty – we cannot take that away – but we can and should attempt to remove layers of dispute in certain circumstances.

For instance, if we were to make pre-nuptial agreements more enforceable in certain circumstances, this would lead to more certain, less disputed and less costly outcomes.

Prenups are a whole other discussion, but we do need people to be thinking ahead of their marriage as to what outcomes would be desirable in the event of a breakdown, and to be recording this thinking.

All this means that there is still a lot that we have as a society to discuss when it comes to divorce.

If the result of the new legislation is to take away the sting and emotional upset of blame-based divorce, but to increase the duration of an upsetting and destabilising process is that the best result?

And if, after all this, the suffering caused by lengthy disputes the division of assets still goes on, have we done enough?

Covid will prompt the review of many of our institutions, and the divorce courts should not be immune to this process.”

Jane has further been quoted discussing this bill in our article “Jane McDonagh quoted in Family Law regarding the newly passed ‘No-Fault’ Divorce Bill” and in Latest Law’s article, “UK: Divorce Lawyer praises landmark ‘no-fault’ divorce bill amid outcry from MPs”. Please do not hesitate to contact Jane McDonagh, or any of our Family Law team, if you would like advice on this matter.

Other News

-

21st January 2021 Dispute Resolution, Media & Communications Disputes

All in on blackjack.com pays off with big win

In a judgment handed down on Tuesday 19th January, SMB won a claim to recover the domain name blackjack.com on behalf of our client, Hanger Holdings.

Read more -

22nd January 2024 Corporate, Commercial & Finance

SMB helps Interaction Recruitment’s acquisition trail

SMB acted for Interaction Recruitment in its acquisition of highly regarded recruitment businesses, Hamilton Mayday and Lifeline Recruitment.

Read more -

2nd February 2021 Media

SMB advises on the production and financing of new film “Save The Cinema” for Sky Cinema starring Samantha Morton, Tom Felton and Jonathan Pryce

SMB’s Media Team have advised FAE Film and Television Limited on the production and financing of new film Save The Cinema for Sky Cinema.

Read more